Introduction to Trustworthy AI

Introduction to Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence

1. The Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI

The European Union's High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence proposed a framework for Trustworthy AI, the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, to provide guidance on the development of human-centered and ethical AI systems. Trustworthy AI is AI where users and affected people can trust that the system and the people and processes behind the system are aligned with the foundational European values of respect for human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. Similar to other high-risk sectors, such as aviation, nuclear power, or food safety, one cannot look at the technical components in isolation, but also has to consider the complete context where they are used.

To be considered trustworthy under the EU framework, an AI system should meet three objectives during its complete lifecycle. (1) It should comply with applicable laws and regulations, (2) it should adhere to ethical principles and values, and (3) it should be robust, both technically and from a social perspective.

The Ethics Guidelines introduce four ethical principles as high-level goals of ethical AI systems, as well as seven key requirements with sub-requirements for concrete AI systems that want to implement these high-level goals.

1.1 Ethical Principles of Trustworthy AI

The four ethical principles of Trustworthy AI are rooted in the EU fundamental rights which AI practitioners should adhere to: (1) Respect for human autonomy, (2) prevention of harm, (3) fairness, and (4) explicability. These principles are already partially reflected in existing laws, but also cover additional dimensions, as laws can sometimes be slow to adapt to technical developments, and just because something is not illegal might not necessarily make it ethical.

The first principle is respect for human autonomy. Freedom and autonomy of human beings are core values of our western modern democratic society. Interactions with AI systems should therefore not hinder humans to make self-determined decisions. They should especially not deceive, manipulate, condition or coerce humans, but instead augment, complement and empower their skills.

The second principle is prevention of harm. AI systems should not cause harm or adversely affect humans, both physically and mentally, and AI systems should aim to protect human dignity. This also means that AI should only be used in safe and secure environments and that the systems should not be open to malicious use. In addition, special effort should be made to avoid adverse impact in situations with asymmetric power or information, in the healthcare sector for example in situations between clinicians and patients, where the clinicians generally have more power and information than the patients.

The third ethical principle is fairness. Fair development and use

of AI systems means for example, that there should be an equal distribution of

costs and benefits between the different groups of society. It should also be

ensured that there is no unfair bias, discrimination or stigmatization against

certain groups or individuals, and no one should be deceived or impaired in

their freedom of choice. Fairness also means fostering equal access to the

developed technologies and the proportionality and balance between competing

interests. Furthermore, fair AI systems also allow for the ability to contest

their decisions or to seek redress against the system and the humans operating

it.

The fourth ethical principle is explicability. This principle is not specific to the AI system, but also includes the processes where it is used, and communication related to the system. An explicable AI system can explain its decision process, is used in transparent processes, and its purpose, capabilities and limitations are openly communicated. Explicability is therefore an important part not only of the AI system being trustworthy, but also on ensuring and enhancing the users’ trust. This is especially the case in healthcare, where the AI system can be interacting with highly skilled professionals who want to understand how applicable the AI system’s decision is. The decisions of explicable AI systems are also much easier to communicate to patients than the decisions of non-explicable ones.

1.2 Tensions between Ethical Principles

All of the four ethical principles share the same importance. However, in practice it can happen that there is a conflict between different principles. For example, when comparing two systems, the less transparent system could have a better clinical performance, which would then lead to a conflict between the principle of prevention of harm and the principle of explicability, where the principle of harm would require the use of the more accurate system, and the principle of explicability would require the use of the more transparent system. In some cases, this tension can be resolved, for example by increasing the system’s transparency or collecting additional data and training the system to better performance. In other cases, there might exist no clear solution to such a dilemma. In these cases, it is important to have a reasoned, evidence-based reflection on the possible trade-offs with a multitude of stakeholders and to openly communicate the trade-offs taken.

1.3 Key Requirements of Trustworthy AI

The ethical principles for trustworthy AI provide a very high-level goal

for AI systems to strive towards. However, it is not immediately obvious what

these principles can entail, which components of an AI system might be related

to them and how one would consider and implement these principles during

development. Therefore the Ethics Guidelines also provide a list of practical key requirements AI systems need to fulfill in order to be considered trustworthy under

the proposed EU framework.

AI engineers can then use these requirements during design and development of AI systems to strive towards ethical applications of the technology. Managers can use them to ensure that the systems they deploy in their facilities follow ethical standards, and clinicians and patients can use these requirements to assess whether the AI systems they are using or that are used on them are trustworthy.

The requirement for human agency and oversight is derived from the ethical principle of respect for human autonomy. Requiring human agency and oversight entails that an AI system should foster fundamental rights, support the user’s agency and allow for human oversight. If there is ever the risk that the AI system impacts fundamental human rights, such as the prohibition of unfair discrimination or access to healthcare, an evaluation of the risks and whether they are justified and necessary should be undertaken prior to the development of the AI system. Support of users’ agency can come in multiple forms. For one, user autonomy should be central to the functionality of AI systems. AI systems should enable users to make better and more informed choices, they should not be used to manipulate them. In addition, the users should be provided with the knowledge and tools to be able to interact with the system and self-assess its decisions. The goal of AI systems should be to provide them with support to make better, and more informed choices.AI systems should also always allow for human oversight. This means that humans should be able to decide if they want to use the system and they should be free to overrule the AI’s decisions.

The requirement of technical robustness and safety is derived from the ethical principle of prevention of harm. It includes resilience to attacks, fall back plans, accuracy, as well as reliability and reproducibility. Technically robust AI systems are developed to minimize unintentional harm, coming from, for example, unexpected situations, changes in their environment, or adversarial behavior. This means that these systems are protected against attacks, such as hacking and other malicious changes, and potential abuse is taken into consideration. There should also always be a fallback plan if something goes wrong with the system, and there should be a process to assess and communicate the potential risks related to the use of the AI system. Moreover, the AI system should perform its task with a high accuracy. This accuracy should be well-validated to mitigate risks from false predictions. Ideally, the system can also communicate how likely it is making an error in different situations and its high accuracy can be reproduced by an independent party.

Another requirement derived from the principle of prevention of harm is the requirement for privacy and data governance, which includes respect for privacy, integrity of data and controlled access to data. Privacy and data protection are especially important, as AI systems, and especially those in healthcare, are often working on and with highly sensitive personal data. It must therefore be ensured that this data is not used for unlawful or unfair actions. At the same time, the quality of the data must be assessed and ensured, as AI systems are only as good as the data they are built with and feeding it malicious data might change its behavior in unexpected ways.

Transparency is required through the ethical principle of explicability. This requirement includes traceability, explainability, and communication. A transparent AI system is one where the AI’s decision process, as well as how and where it influences human decisions is explainable. These explanations should also be understandable by both clinicians and patients. In addition to the AI’s decision process, it should also be documented what data the AI was trained on, to better identify reasons why a given decision might be correct, or erroneous. Most important, however, is communication. This means that AI systems should always be identifiable as AIs and not pretend to be humans, and it should be clear why they are used and what their capabilities and limitations are.

The ethical principle of fairness translates well into a requirement for diversity, non-discrimination, and fairness, implemented through the avoidance of unfair bias, accessibility, and stakeholder design. AI systems should avoid unfair biases, which can for example arise by using old or incomplete datasets, and they should not be used to discriminate against people or exploit them. In addition, the AI systems should be tailored towards the needs of their users. They should not be developed in isolation, but in cooperation with as many affected stakeholders as possible. There should also be mechanisms for ongoing inclusion of feedback, even after system deployment.

The

principle for societal and environmental well-being is in line with the

principles of fairness and prevention of harm. It includes environmental

friendliness, social impact, and impact on society and democracy. Ideally,

the benefits of AI systems should not be realized at the expense of the

environment or future generations. Training and running AI systems can require

immense amounts of computational power and therefore energy. It is advised to

be aware of this fact and try to reduce its impact, whenever possible. AI

systems can also alter social interactions, their effect on the physical and

mental wellbeing of its users should therefore be monitored.

Another requirement derived from the principle of fairness is accountability. It complements the other principles and ensures that responsibility and accountability for AI systems and their outcomes are taken, before, during, and after their use. This is realized with auditability, reporting of negative impacts, trade-offs, and redress. Accountability can be fostered by having audits or assessments of the AI system, ideally by an independent party. The results of such reports can then be made publicly available to increase trust from potential users and the general public in the system. In many cases during the design of the system, or the implementation of requirements for trustworthy AI, trade-offs will have to be made. In such cases, the trade-offs, as well as the reasoning behind their resolution, should be openly communicated. It should also be clearly communicated who is responsible for the trade-offs, and this responsible person should continually review whether the trade-offs are still appropriate. During use of the system, it should also be possible to report actions that led to a negative outcome, so the developers are aware of them and can work on preventing them in the future, and in cases where the AI’s decisions are negatively impacting an individual, it must be possible for them to seek redress.

2. Z-Inspection® - A Process to Assess Trustworthy AI in Practice

Trust between AI systems and the humans that use them is essential to successful and beneficial applications of AI, not only in healthcare. With their Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, the EU high-level expert group on artificial intelligence provides requirements that AI systems should fulfill in order to be considered trustworthy. However, for practical applications in healthcare, these guidelines and requirements can still prove too abstract. In addition, it can happen that clinicians will be asked to use an AI system where they did not participate in any step of the design and development process and might therefore have reservations towards trusting the claims put forth by the vendor.

Even

though the ethical principles and requirements proposed in the ethics

guidelines are on a very abstract level, they provide a cohesive framework for

the assessment of trustworthy AI. This makes them suitable as foundations for

more practically oriented assessment processes.

Z-Inspection® is tailored towards the challenges and requirements of real-world systems development and can be used for co-design, self-assessment, or external auditing of AI systems. This makes it well-suited as a general-purpose methodology that can be used for assessing and improving trustworthiness of AI systems during their complete lifecycle. In the design phase, Z-Inspection® can provide insights in how to design a trustworthy AI system. During development the process can be used to verify and test ethical system development and to assess acceptance by relevant user groups. The process can also be used after deployment as an ongoing monitoring effort to inspect the influences of changing models, data, or environments.

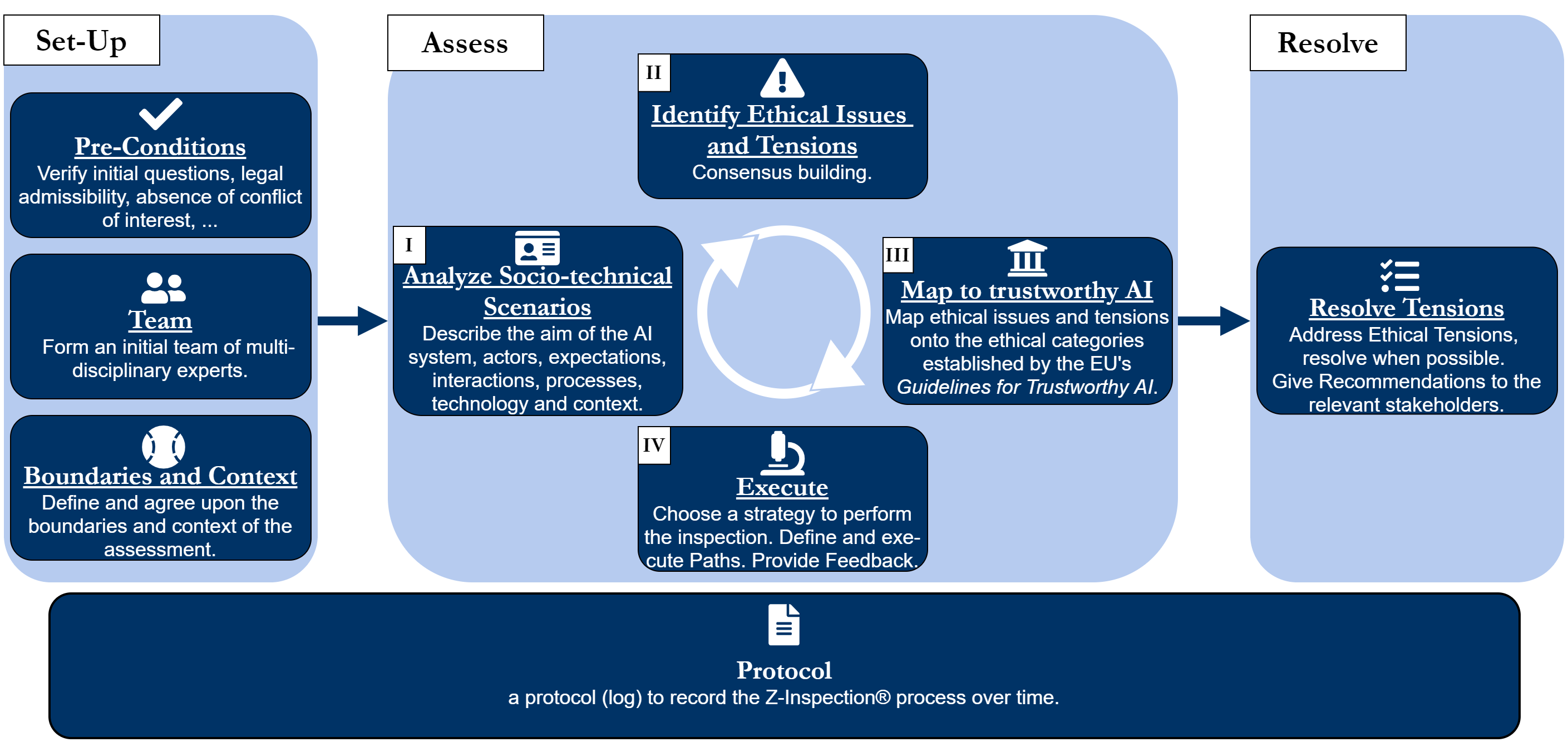

The process consists of three main phases, which will be presented in greater detail in the following: (1) the setup phase for clarifying the preconditions, identifying the assessment team, and agreeing on the boundaries, (2) the assess phase where the AI system is analyzed, and (3) the resolve phase, where the identified issues and tensions are addressed, and recommendations are produced. A schematic overview of this process can be seen below.

2.1 The Set-Up Phase

The first phase of the assessment process is the set-up phase. It begins with the identification of an assessment team of experts from different disciplines. As the application of AI systems touches many sensitive areas, it is advisable to have experts from these areas.

The next step is to align everyone on the goals of the assessment and to make the stakeholders aware of what is expected from them. Important points to align on are for example “who requested the inspection”, so whether the assessment is performed on a mandatory or voluntary basis, and if it was requested by leadership, developers, or others. Another important point to align on is, for example, “how are the inspection results to be used”. Are they used for public advertisement, system improvements, communication with end-users, or other things?

The final step of the set-up phase is then to define the boundaries of the assessment. The AI is not used in isolation, so it is important to also assess the socio-technical environment it is used in. Excluding parts of this socio-technical environment can have far reaching implications for the further course of the assessment. Doing so should therefore be reasoned and communicated with the participants.

2.2 The Assess Phase

The second phase of the assessment process is the assess phase. It is an iterative process consisting of multiple steps: (1) definition of socio-technical scenarios under analysis, (2) analysis of the scenarios to identify issues, (3) mapping of the issues to the trustworthy AI guidelines, and (4) consolidation of issues.

The first step of the assess phase is to define socio-technical scenarios that describe possible everyday experiences of people using the AI. These scenarios will be used to anticipate and highlight possible problems that could arise from use of the AI. The scenarios are based on available information provided by the vendor, personal experience of the participants, and the boundaries of the assessment as defined earlier.Then, the issues are mapped to the requirements for trustworthy AI they are in conflict with. This helps to highlight tensions between the system’s behavior and the requirements for trustworthy AI. The mapping step is of central importance to the assessment process. Before, the domain-specific risks are expressed in a free vocabulary from the point of view of the different experts. However, they do not necessarily have the background to foresee the ethical implications of these issues that can impact the trustworthiness of the system. With the mapping, it is described why a problem can impact the trustworthiness of the system, using the closed vocabulary of the framework of the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI. This means that if a problem discovered by experts can be mapped to one of the key requirements for trustworthy AI, performing the mapping is also arguing which of the key requirements the system is in conflict with, and how this conflict is impacting the trustworthiness of the system. This in turn makes it possible for non-ethicists to contribute to an ethical discussion on how problems with the system can impact its trustworthiness.

Finally, the issues found in this step are consolidated. Each of the different stakeholders or groups of stakeholders presents their issues to the others and issues describing similar problems can be combined to make the list of issues more concise.

2.3 The Resolve Phase

The final phase of the assessment is the resolve phase. Based on the consolidated list of issues developed as a result of the assess phase, the participants discuss as a group which of them are the most pressing and how they can possibly be resolved. In some of these issues it can become apparent that there is a tension between different principles. Depending on the system and the issue, one of three cases can occur: (1) the tension has no resolution, (2) the tension could be overcome through the allocation of additional resources, or (3) there is a solution beyond choosing between the two conflicting principles. In some cases, there might be an obvious solution to the conflict, in others a solution might be impossible or require a trade-off. Here the participants explicitly address the ethical tensions and required trade-offs with the other stakeholders and provide recommendations on how to mitigate their impact.

At this point, the assessment process is complete. It is now up to the other stakeholders what they want to do with the results and recommendations of the assessment. As this process is used for voluntary self-assessments, it is up to the stakeholders to decide on what recommendations they want to act.

3. Further Reading

- High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, “Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI,” European Commission, Text, Apr. 2019. Accessed: Oct. 26, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d3988569-0434-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1

- High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, “Assessment List for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (ALTAI) for self-assessment,” European Commission, Text, Jul. 2020. Accessed: Feb. 09, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=68342

- R. V. Zicari et al., “Z-Inspection®: A Process to Assess Trustworthy AI,” IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 83–97, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TTS.2021.3066209.

- R. V. Zicari et al., “How to Assess Trustworthy AI in Practice.” arXiv, Jun. 28, 2022. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2206.09887.